“We wouldn’t hit land mass until Bueno Aires.”

I am jolted back to the moment as my mind tunes into the voices coming through my headset.

Huh? What’s South America got to do with it? I am several thousand feet above Cradle Mountain and a million miles away.

“So we wouldn’t hit the Cape of Good Hope?”

“No, we’d go under it.”

Hoey, our pilot, has explained that if we were to fly due west, with plenty of fuel of course, after leaving Tasmania we wouldn’t hit land until South America.

In the last 15 minutes Hoey has told us the story behind Cradle’s distinctive shape, pointed out the fagus plants that will colour the valley in autumn and explained why the pools of water dotted on the plateau below us are brown.

I’m listening. I am. But I also can’t stop looking out the window.

Cradle Mountain is the most recognisable sight in Tasmania. I don’t have to say ‘arguably’ because no one will argue with me. It’s iconic. It is the image that represents my state. That mountain graces postcards, calendars and Instagram like it’s the only thing in Tassie to photograph. When Lonely Planet named Tasmania as the fourth best region to visit in 2015 – it was a picture of Cradle Mountain that illustrated the point.

Thanks to this dizzying array of images I’ve seen Cradle Mountain at sunrise and sunset, bathed in sunshine, reflected in a glass-like Dove Lake, dusted with snow and blanketed in white.

But Cradle Mountain from 6000 feet?

This is Cradle Mountain as I’ve never seen it.

After rising from the helipad at the visitor centre, it doesn’t take long before I have a stunning panorama looking west. The weather is forecast to turn later, but for now it’s blue skies with little cloud.

Hoey heads south and through the front windows I see Cradle in the distance. We get closer and I have a few moments to take a photo of the iconic mountain before we turn into a valley and Cradle disappears from view.

The helicopter swirls a little as we enter Fury Gorge, one of the deepest gorges in Australia. It’s my first time in a helicopter and despite my aversion to heights I feel safe, mostly thanks to Hoey’s warnings of any bumpy bits and his assurance they won’t last long.

This is Hoey’s first tourism-based pilot gig, but he’s a natural tour guide. But his knowledge of the landscape and the history is nothing compared to his passion for the area.

He later tells me this is some of the best flying in Australia.

”It’s just magic. I love it.”

In Fury Gorge the sensation of being up in the air changes. I’m no longer looking down. The gorge is so deep that as we fly through it, I feel as if I’m in it. I can look straight out to the tapestry of trees on the sides of the valley or at a waterfall fed by the melting of the snow from last week, or even up, to some of the rocky cliff faces.

When we emerge from the gorge the panorama returns, as does our bird’s eye view.

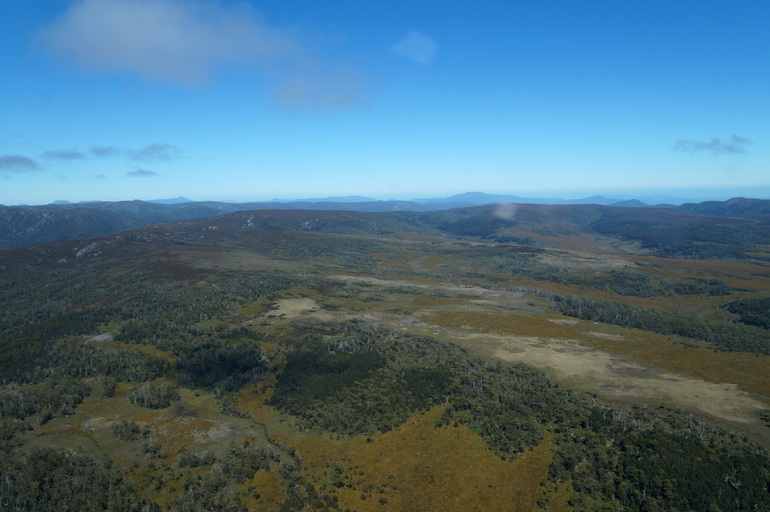

Soon we are behind Cradle Mountain, looking down on a plateau of button grass and brown tarns. “When it rains, it washes through the peat and causes the stain in the water,” Hoey explains.

He points out the track and huts along the Overland Track, the 65-kilometre walk from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair that I’ll become very acquainted with over six days in January.

As Hoey points out the hut for the second night of the walk, I try not to think about to difference in covering this ground on foot compared to buzzing over it in a helicopter.

It’s about here I start to tune out, not because I’m not interested, but because I’m mesmorised by the view. When imagining seeing Cradle Mountain from the air I had pictured exactly that. I hadn’t thought about what lay beyond.

I’ve visited Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, part of the UNESCO-listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, many times, but done relatively little exploring. The sheer size of the area and the challenging terrain makes it difficult.

As a reporter at the local newspaper I wrote far too many stories about people running into difficulties while walking here. They were usually unprepared and underestimated what they were in for. I can recall, unfortunately, more than one fatality. So most of the walks I have done in the area have been low-level in dense surroundings that didn’t offer much of a view.

For better or worse, so much of the Tasmanian wilderness is inaccessible to anyone but experienced hikers. Having never climbed any of the lookouts or summits around Cradle Mountain, this landscape is new to me. And it’s stunning.

The faintest touch of snow glistens on the south side of Cradle, unlikely to last much longer. In a day or two it will fall victim to the sun that’s causing such a shimmer on the tarns below. “I prefer it when there’s a little bit of snow, not completely covered,” Hoey says. “Otherwise you lose that contrast.”

The company operated during the winter and there were days when the snow was so thick Hoey couldn’t land on the helipad. Here, though, the snow isn’t reserved for the winter. Two weeks after my spring flight, Cradle was once against dusted with the white stuff.

As Hoey turns for home, he points out what lies ahead of us – much, much ahead of us. Bueno Aires. It’s another reminder of our location at what feels like the bottom of the world sometimes.

The clouds have moved in during our time in the air. On a clear day we could have seen much more to the Coast, but instead our horizon is white and fluffy, another reminder of my rare perspective from up here.

Cradle Mountain Helicopters operates from the visitor centre at Cradle Mountain. A 20-minute scenic flight costs $245 per person, for between two and four passengers (depending on the type of helicopter). You can check out the Facebook page here.

I was a guest of Cradle Mountain Helicopters, but not for the purpose of writing this article. All opinions expressed on Pegs on the Line – and my friends will tell you I always have a lot – are my own.