The scorched, red earth around William Creek bears the scars of drought. The wind has eroded the soil. The stations have cut their herd numbers.

The big dry is punishing. But due east, there is water. Stacks of it.

The rain that devastated regions up north earlier in the year is bringing life to Australia’s biggest lake.

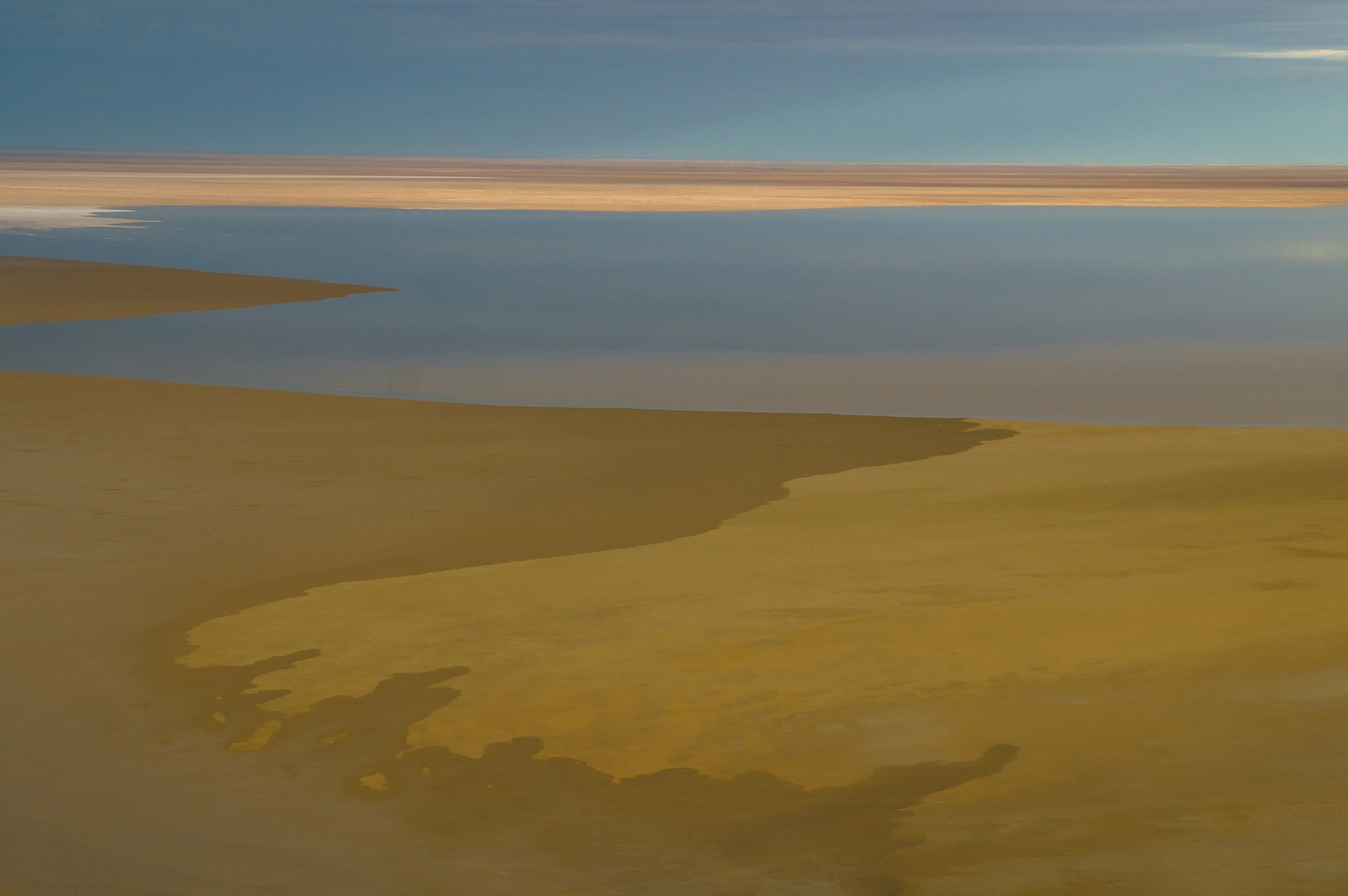

Most of the time, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre is a glistening salt pan in the South Australian outback. An expanse of white as far as the eye can see. But when enough water flows through the web of rivers that feed it, the lake starts to fill.

Almost two years ago I flew over Lake Eyre from Coober Pedy. It was dry then, but the sight of its sparkling surface and milky swirls where the salt wove into the land was extraordinary .

But Lake Eyre in flood is a phenomenon and witnessing it is a dream that’s brought me back to William Creek, a tiny town along the Oodnadatta Track.

A desert flooded

The flies don’t wait for the sun as pilot Trevor Wright, owner of Wrights Air (and the rest of the town), prepares our plane on the tarmac while the sunrise changes from purple to red. There’s clouds in the sky and word of storms in the west.

By the time the six-seater Cessna scoots down the airstrip – the only sealed road for hundreds of kilometres – the sun has peaked above the horizon and we fly straight into it.

It highlights the dunes in the dusty, deep red land of Anna Creek Station, the world’s largest cattle station. There are fewer cattle at the moment, Wright tells us. The expected rain didn’t come so the station has cut stock.

From several hundred feet in the air Wright points out the small white mounds in the dirt – rabbit warrens.

The flight is smooth. Our early start means the earth below hasn’t heated up enough to create the pockets of turbulence that might have made me regret breakfast.

It takes about 15 minutes to reach the south-west edge of Lake Eyre North, where the parched brown earth gives way to a sweeping stretch of white salt. And beyond that … water.

While water in the lake isn’t uncommon, a flood with the potential to fill an area four times the size of the Australian Capital Territory occurs only three or four times in a century. The last was in 1974.

In March this year the first stream of water from the monsoonal rain that drenched Queensland in January reached the northern end of the lake. In April the Lake Eyre Yacht Club (yes, there is such a club) held its first regatta in three years. A second wave, the legacy of Cyclone Trevor, is due this month, and it’s this impending arrival that has many predicting the biggest flood in Lake Eyre in four decades.

A rim of foam, like waves breaking on the beach but in this case a result of the cracking salt crust, lines the water’s edge. It doesn’t look that far from land, but the lake hasn’t filled enough to be seen from the end of the 60-kilometre track at Halligan Bay.

But from the air the view is spectacular; the light sky and soft clouds are perfectly reflected on the lake’s surface.

“Wow,” Wright says. “I’m impressed. It’s hard to believe you’re over a drought-affected area of South Australia and here you are with this huge expanse of water and a pristine river system.”

Wright’s been flying over the outback for decades and speaks about the land and the spectacle of Lake Eyre with passion, even though he’s seen it countless times. He joins us in excitedly taking photos through the windows. “I haven’t been out here for a few weeks,” he explains.

Coming to life

As we fly across Belt Bay Wright delights in showing us Australia’s lowest point – 15.2 metres below sea level – covered with water, before pointing out a pelican rookery on Silcrete Island. He loops around for a better look.

There are close to 100 grouped in the water, little more than specks of black and white from the sky.

The birdlife isn’t a surprise, but it’s still odd to see them, especially having just flown over such dry, barren land on our way to the lake this morning. But it’s all part of the transformation of Lake Eyre.

The water brings so much life – fish, frogs, birds; some of which arrived almost before the flood. “It’s funny how the birds know about it,” Wright muses.

He spots some tracks in clay yet to be covered by water. “You get some crazy emus here.”

We fly over black swans, ducks, banded stilts and more pelicans. Some are spooked by the plane and take flight, leaving ripples in the water behind them.

Birds will nest their young as the lake fills, feeding on the brine shrimp in the lake.

“When [the lake] is full it can handle millions of birds,” Wright says. “The islands turn into breeding grounds.”

The sheer number of the birds, which Wright hasn’t seen for a long time, gives him optimism there’s more water to come.

“It’s a novelty to see so much water out here. It’s so out of context with the reality of the harshness of the environment.”

Outback pilgrimage

The water and the birds aren’t the only things flooding into Lake Eyre.

Tourists are rolling into William Creek every day and will continue to until the searing outback heat kicks in about October.

The town, originally a stop along the old Ghan railway line, is officially home to 10 permanent residents. The population swells during winter when the weather is mild. In the summer, when temperatures can regularly top 40 degrees, there’s more planes than people, Wright jokes.

It’s two-and-a-half hours to Coober Pedy and the nearest supermarket. The Oodnadatta Track will take three-and-a-half to Oodnadatta in the west or Marree in the east. Whichever road you go down, it will be dirt.

The quintessential quirky outback town is a popular stop for off-road adventurers, but more people than usual are making the pilgrimage to see Lake Eyre in flood. Bucket lists are mentioned.

Wright, who also owns the William Creek Hotel and campground (which is about all there is to William Creek), is still surprised at the number of tourists.

“When I came out here 30 years ago, I never thought in my wildest dreams I’d still be here 30 years later … in a micro-township in the middle of nowhere.

“But it’s amazing what you can do with a bit of vision.”

Wright says flights from Marree are popular as people also want to see the Marree Man, a 4.2-kilometre tall etch in the landscape mysteriously created 21 years ago. His pilots at Wilpena Pound in the Flinders Ranges are also busy. Only five hours from Adelaide on sealed road, it’s one of the most accessible departure locations to see Lake Eyre.

During the day in William Creek the sound of planes is constant. Road trains rumble down the dirt “main street”. A few visitors poke around the Memorial Park; an outdoor museum containing the remains of the Black Arrow rocket, successfully launched from the Woomera Rocket Range in 1971. No one takes a hit at the golf course, a dry, dusty clearing next to the fuel pumps.

At night the pub heaves with tour groups, Baby Boomers, outback pilots and workers from the nearby station. Wright pops in most evenings to chat.

Nearly everyone we meet is taking a flight over the lake. Some grab a rare spare seat as soon as they arrive in town. Others wait a couple of days for a spot to open up; biding their time in fold-up chairs outside their caravans with fly nets over their head.

A natural spectacle

As we fly up the Warburton Groove, a wide channel running down the middle of the lake, the view reduces to lines – water, sand, earth, sky. It looks like a painting. Nature’s version of abstract expressionism. The horizon seems to disappear.

“You get a lot of visual illusions when you’re flying around the lake,” Wright says.

The appeal of seeing Lake Eyre in flood is both the infrequency and the spectacle.

The colours change as the sun gets higher. We don’t see the pink, purple or bright yellow I’ve seen in photos. Instead the water morphs between soft blues and greys, reflecting the sky and clouds like a mirror.

On my first visit to Lake Eyre in 2017 its sheer size blew me away. I struggled to take it all in, knowing we were seeing only a fraction of the 9500-square-kilometre lake. It happens again as we follow the groove.

We’re travelling about 300km/h, Wright reminds us, and we are over water for a long time as we head north.

The birdlife increases as we near the mouths of the rivers responsible for carrying this water across the country. Dark green fringes line the edges of Warburton and Kallakoopah creeks, part of the labyrinth of waterways that feed Lake Eyre. Sawtooth dunes show where the water has forced its way over the desert.

It takes 30 days for water coming in from the rivers to reach Belt Bay when the surface is dry. Now there’s water in the lake, the groove acts as a freeway, Wright explains.

Images from NASA taken three days before our flight in May showed the lake was half full. It’s thought to be about 1.6m deep in Belt Bay and the second flood due this month could push that to two metres.

Will it be enough to surpass the flood of ’74? Wright’s not sure, but he expects it to be significant. Cooler temperatures and less evaporation will mean what water is in the lake should linger. “If we don’t get substantial rains by November, December, this will all disappear over Christmas,” Wright says.

There is rain in the distance as we fly down the west side of the lake. In another display of the enormity of Lake Eyre, after leaving the rivers at the north, we travel over water for about 30 minutes before returning to the scorched, red earth.

If you go

Wrights Air flies over Lake Eyre from William Creek, Coober Pedy and Wilpena Pound. Coober Pedy and Wilpena Pound can be accessed by sealed roads. Driving to William Creek requires a 4WD.

Lake Eyre floods to 1.5m about every three years, and to 4m every 10. It will fill only three or four times in a century. The Lake Eyre Yacht Club monitors water levels in the lake on its website.

This article was first published at The Canberra Times.