It’s the biggest lake in Australia and one of the largest in the world. It sits in the middle of the desert, yet can be as salty as the sea. It’s visible from space and has filled just four times in the last century.

Yet, Lake Eyre often contains little to no water.

Most years, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre is a white expanse in the South Australian desert; a dry salt pan marking the lowest point on the Australian mainland.

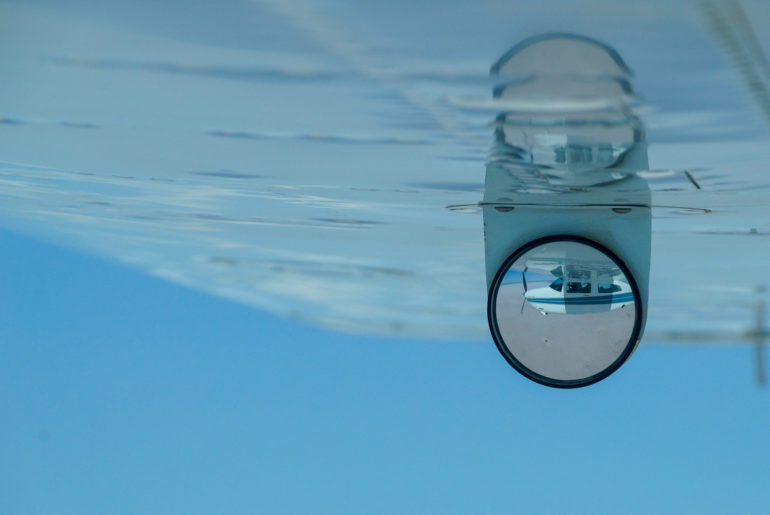

It can be reached by road off the Oodnadatta Track, a 617km dirt road between Marree and Marla best tackled in a 4WD. But the most popular way of seeing this outback phenomenon is from the air.

We hopped in a four-seater prop plane at Coober Pedy, saving ourselves a day’s drive to William Creek, another common departure point. Wrights Air also offers flights over Lake Eyre from Wilpena Pound in South Australia’s Flinders Ranges.

Anna CreEk Painted Hills

Flying out of Coober Pedy, where from above the opal mine shafts looked like ant mounds, we headed for the Anna Creek Painted Hills. The flat, burnt red landscape gave way to marbled ranges of ochre, terracotta and white. Streaks of dark green trees lined the valleys formed long ago by rivers carving their path.

The Painted Hills are not dissimilar to The Kanku-Breakaways just north of Coober Pedy or the Painted Desert, a little farther north. The area was once covered by an inland sea, and tens of millions of years of erosion and tectonic movements have sculptured the landscape. The spectacular colours are attributed to oxidised minerals.

The Painted Hills are part of Anna Creek Station, the biggest cattle station in the world. The hills were discovered only about 13 years ago and the exact location remains a secret to protect the fragility of the site. For many years the only way to see the hills was from the air, but small-group ground tours began last year.

The landscape got more impressive the lower we flew, but so did the turbulence as the plane hit pockets of heat radiating off the desert earth.

William Creek

A small grouping of rooftops in the distance turned out to be William Creek, an iconic outback town on the Oodnadatta Track.

The airstrip is the only sealed road in town and runs behind the back of the local pub and the Wrights Air office; two of only a handful of buildings in William Creek. It was once on the old Ghan railway line, but the new track runs a lot more to the west now.

The town, if we can call it that, claims to be the smallest in Australia and lives up the reputation places like this earn as ‘quirky’. It has a permanent population of about 10 people. During the tourist season, a contingent of outback pilots call this place home as they rack up their hours flying over this unforgiving terrain. Their sharehouse accounts for one of the other buildings.

‘The main street’ is lined with trees, all planted by Trevor Wright, the owner of Wrights Air, when he moved to William Creek. He’s since also taken over the William Creek Hotel, the only place in town to get a bite to eat. It was meant to be our lunch stop, but feeling a little green from the first leg we played it safe with ginger beer and salty chips.

The pub is decorated in typical outback fashion, plastered with signs, business cards, handwritten notes on scraps of paper. Across the road is a campground and the Memorial Park, which displays the remains of the Black Arrow rocket, successfully launched from the Woomera Rocket Range in 1971. A rusted sign stands in front of a dry, dusty clearing posing as the William Creek Golf Course.

Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre

We had flown over red and brown desert plains of dust, dirt and gibber rock. But that changed when we crossed the edge of Lake Eyre and the view below us turned white.

The dry lake bed, glistening under the sun, stretched to the horizon, with cracks, stains and swirls where the salt had washed over the parched brown land. It’s a view that greets most visitors to Lake Eyre.

Lake Eyre is fed by a web of rivers stretching into South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory. It’s normally dry, or has only a small amount of water often not visible from the air.

But every few years, enough water flows down that web to bring Lake Eyre to life.

A flood of 1.5m occurs about every three years, and to 4m every 10. It will fill only three or four times in a century. Those waters can change the colour of the lake, from pink to blue, attract birds and wildlife, and spark life in the surrounding landscape.

The last flood was in 2018 – a year after our flight – when rain that fell in Queensland two months earlier finally trickled down the river system for a once-in-a-decade event.

For us, the view was all white as we flew over Belt Bay and Madigan Gulf, near where Donald Campbell set the land speed record in 1964. We continued over the Warburton Groove and Halligan Bay, before turning back for Coober Pedy.