Standing atop a rocky outcrop in the south-west region of Boodjamulla National Park, it’s beyond my powers of imagination to picture how the landscape before me once looked.

This was rainforest:

And this was a lake:

Actually, to be precise it was mud at the bottom of a lake.

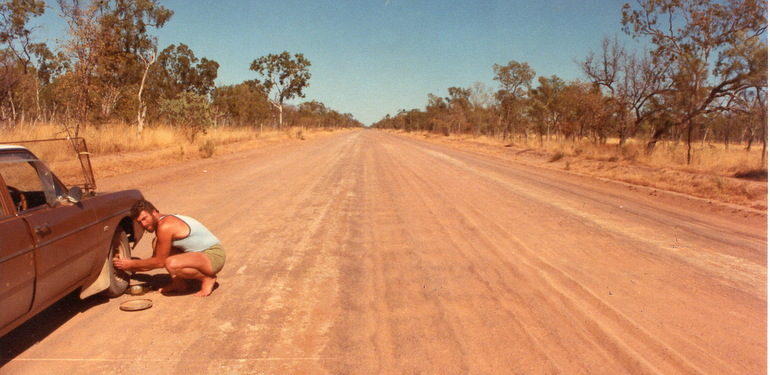

Fast-forward 10 million years and it has transformed into a semi-arid expanse of yellow grass, faded green trees and a bumpy gravel road.

But that lush, tropical landscape left its mark.

In fact it left thousands of them.

Riversleigh is one of the world’s richest fossil mammal sites in the world. More than 60,000 fossil specimens belonging to about 300 kinds of animals have been discovered here since exploration began in the 1960s. The area is part of the World Heritage-listed Australian Fossil Mammal Site, along with Naracoorte Caves in South Australia. I could tell you about so many World Heritage Sites around the world, but I had no idea this existed in my own country. Not a clue. But then to look at the site you couldn’t possibly know there was anything significant here.

D-Site is the only area at Riversleigh that’s open to the public and consists of a concrete information centre and toilet, built to blend into the landscape, and a circular walking trail around and over the rocky outcrop. It’s accessible in the sense there’s a road running straight past the car park, but it’s still a four-hour drive to Mount Isa, the nearest town of a decent size. And that’s still 1800km from Brisbane. So it’s not surprising there are only two cars parked when we arrive and after they leave we don’t see another person or vehicle.

The fossils collected at Riversleigh were preserved in limestone and tell countless stories.

The discoveries have provided answers to questions researchers had stopped asking. The Thylacine (also known as the Tasmanian Tiger) was hunted to extinction last century and was thought to be the only Tertiary thylacine species until different thylacines were discovered at Riversleigh.

The site has also created lots of new questions. The fossil of one creature, called “Thingodonta”, doesn’t appear to belong to any of the known marsupial families. Scientists have actually given the unknown animal its own family.

Many of the fossils here have been removed and placed in museums, but a small selection remains at Riversleigh.

Brushing flies from my face, I walked along the trail to the first fossil, stopping in front of a white circle of bone embedded in a rock. It was the cross-section of a limb bone from a freshwater crocodile. While there are just two species of crocodile in Australia now – the estuarine crocs that kept me well away from the water in Cape York and Gulf Country, and the “harmless” freshwater crocs – fossils collected at Riversleigh suggested there was at one stage nine species to crocs.

“Is that it?”

The significance of what I was seeing didn’t sink in. I’ll be blunt. I was disappointed.

While I was travelling in Europe I’d visit sites such as the Colosseum in Rome or Ephesus in Turkey and be blown away by the age of what I was looking at. But I’ve always found it much harder to comprehend and appreciate natural history. It sounds ridiculous, but a 20-million-year-old bone fragment embedded into a rock is less impressive at first sight than the remains of a 2000-year-old library.

It isn’t just the fossils that tell of the changes in the landscape here. At the top of the rocky outcrop, two distinct layers of sediment can be seen. The top is limestone, which 25 million years ago would have sat at the bottom of a shallow lake. The bottom layer is conglomerate, which is thought to have been river gravel deposited not long before the lakes formed.

In the hills to the west are examples of what the interpretative sign calls “pancakes”. The rock stacks are Cambrian marine limestone, formed in a shallow inland sea about 530 million years ago. No, I did not type a 0 on the end of that by mistake. These stacks are five-hundred-and-thirty-million years old. Fossils of primitive shellfish were found in these types of rocks, but vertebrate animals were not – because they didn’t exist yet.

I say “wow” now, but at the time I looked at those stacks and thought “uh ok, cool!”

It wasn’t until I saw the last fossil on the trail that I started to absorb the magnitude of the site.

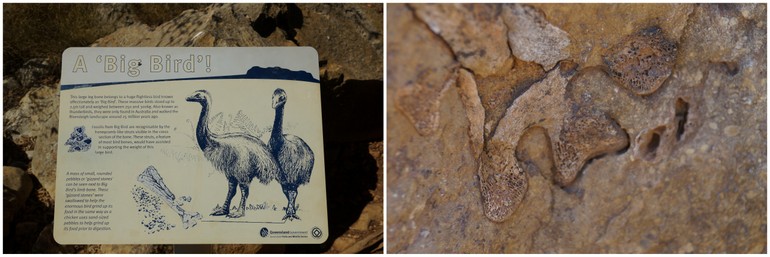

Big Bird.

Once upon a time Australia was home to a flightless bird that stood up to 2.5 metres tall and weighing between 250 and 300 kilograms. None of the information signs or booklets I had gave it a scientific name. They all just called it Big Bird, although the sign at the site said they were also known as thunderbirds, which I have to say, is a pretty awesome name for a bird. A bit of research revealed it is most likely part of the Dromornithidae family and part of Australian megafauna. The Big Bird fossil isn’t even from the biggest bird in the family, which grew to more than three-metres.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. It’s an ancestor of an emu or ostrich or something. Nope. I thought the same thing, but the thunderbirds are not closely related to other flightless birds and actually have more in common with a duck.

There’s no clear answer on why these animals became extinct and most research I read suggested a combination of factors including the arrival of humans and just plain old evolution.

Riversleigh Fossil Site is about 50km south of Lawn Hill Gorge at Boodjamulla National Park. Adel’s Grove Tourist Park operates tours, however we were told the informative signs were enough to help you understand the site without a guide and I agree. If you are coming from Mount Isa or Camooweal, Riversleigh is about 160km north of the Barkly Highway. The roads are mostly gravel. Check road conditions.

Miyumba camp site is a few kilometres south of D Site at Riversleigh, near the Gregory River. It is a very basic camp site, (there is a toilet, but no other facilities). Staying here means you can explore D Site early before it gets too hot. Bookings for the camp site must be made through the Department of National Parks in advance.