More than two decades since the massacre at Srebrenica, the death toll is still rising.

The plaque at the memorial at Potočari reads 8372 – the number of people killed or missing since the 1995 genocide near Srebrenica, in the east of Bosnia and Herzegovina. But the actual number may never be known.

It was Europe’s worst act of genocide since World War II, and has come to define this town in a valley mere kilometres from the Serbian border.

Houses on the drive into town are scarred by bullets and shells. A few are boarded up and hugged by overgrown gardens. They have most likely been empty for the last 23 years; abandoned reminders of the families forced to escape as Bosnian Serb troops descended on the town.

Thermal spring water, supposed to cure ailments such as acne and hair loss, trickles down the same mountains into which those families fled. There was a time when these waters and surrounding pine forest drew tourists.

But that was before.

The horrors at Srebrenica

In 1993, while war raged in Bosnia following the fall of Yugoslavia, the UN declared Srebrenica and its surroundings a “safe area”. Thousands of Muslim Bosniaks, fleeing widespread ethnic cleansing, arrived at the camp seeking protection from the atrocities occurring around the country.

Capturing Srebrenica was a strategic goal for the Bosnian Serb forces and in early July 1995 they succeeded.

The Dutch UN peacekeepers were outmanned and outgunned. By then up to 25,000 Bosniak refugees had gathered at the UN base at Potočari, about seven kilometres from Srebrenica. Their fate was left in the hands of Serb general Ratko Mladić and his army.

Unimaginable crimes – killings, rape, torture – occurred at Potočari. Women and children were eventually separated and bused out of the area. Men and boys of military age were murdered in a series of planned and highly coordinated mass executions.

More than 8000 people, mainly Bosniak men, were killed in 10 days.

The bodies, initially buried in mass graves, were moved to multiple sites, which, even decades later, made it more difficult to identify the victims. By June 2018, the remains of almost 7000 bodies had been identified.

Finally, a resting place

Two police officers stand outside a tiny gift stall across the road from the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial. There is a handful of cars in the small car park, and not many more visitors inside.

The three-hour drive from Sarajevo kept us almost exclusively within the territory of Republika Srpska, the Serb entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Flags in the Serbian tricolours – red, blue and white – flew prominently in even the smallest towns among the farmland and mountains. The same colours were plastered over candidate posters and billboards for the upcoming elections.

But here, outside the site known officially as the Srebrenica–Potočari Memorial and Cemetery for the Victims of the 1995 Genocide, it’s the blue and yellow flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina that flies at half mast at the entrance.

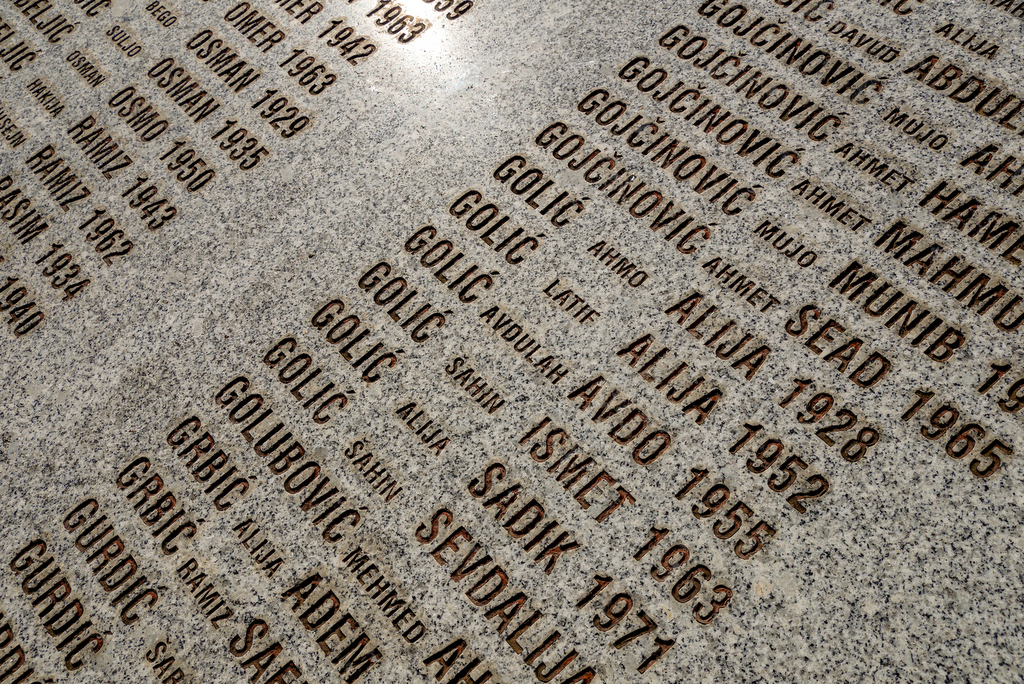

The number 8372 is etched into a commemorative plaque, along with the names of the 13 towns from where the victims came. Under the number, a telling epilogue reads “ukupan broj žrtava koji nije konačan”. The total number of victims that is not final.

When the memorial and cemetery opened in 2003, just 600 victims were buried here. Now about 6500 have been reburied. Burials are held every year and, if the number on the plaque is accurate, the remains of more than 1000 victims are yet to be found or identified.

The names of those victims are carved in a semicircle of huge granite slabs; entire families – fathers, mothers, children – gone. Beyond the names, white headstones stretch row after row into the distance. Smaller green pickets mark the fresh graves. Inscribed on each headstone is a verse from the Quran: “And do not say to those who are killed in Allah’s path: ‘They are dead!’ No, they are alive, but you do not know.”

It’s impossible to comprehend the magnitude of the death here. The horror…it’s too much. After a while I stop reading the names on the tombstones and just take in the scenery. The cemetery is so peaceful and the truth so horrific that I don’t feel affected in the way I thought I would.

But that changes when we walk into the warehouse across the road.

The battery factory

The warehouse was once a factory producing car batteries. During the war it was part of the UN headquarters for the Dutch peacekeepers. Now it is a visitor and exhibition centre.

But for a few chilling days, after the Bosnia Serb troops took control of the camp, it was the scene of a brutal prologue to the massacres. Thousands of Bosniak refugees became hostages here as they awaited their fate. The warehouse, and the complex around it, is where so many of the atrocities I’d read about had taken place.

Compared to the sunny, green cemetery across the road, the warehouse is filled with an inescapable darkness. Whatever feelings I couldn’t get my head around earlier, start to sink in as I look at the bullet holes in the walls.

There are often guided tours, usually given by a survivor, but today the centre is empty. The displays in the Srebrenica Memorial Room include photos from its opening ceremony, attended by then-US president Bill Clinton, and discuss the cases taken to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the ongoing efforts to identify victims and share accounts from survivors – mainly women who were separated from their husbands and fathers and never saw them again.

We study the exhibits mostly in silence. Really, what is there to say?

Perhaps the most moving is the display in the middle of the warehouse. Each exhibit features a photo, a short story of the victim and a personal item found alongside the body.

An engraved pocket watch with a bullet hole.

An old key.

A bracelet.

A wedding ring.

A lot of these items would have been worthless to anyone else. But they were some of the few possessions these people had, and they carried them to the end.

A town in denial

As we drive into Srebrenica, we ask our guide about walking around. He’s noncommittal, adding he’s not sure how the people here would feel about that. He asks for directions to the Guber springs and we head up the ‘promenade’ – a tree-lined narrow road that climbs into the mountains.

At each spring we stop and use our hands to cup water from the streams, splashing it on our face, eyes, hair, as instructed. At the top of the promenade are the bones of a spa hotel where reconstruction stalled years ago. It was meant to be finished in 2012.

The town is quiet, almost eerily so, and there is unmistakable tension. There aren’t many people in the streets. There’s a shopfront for the local tourist organisation and a hostel on the way into town, but this doesn’t seem like a place that wants many visitors. Most people who come here do so because of the massacre. A lot of people who live here want to forget it happened.

From the balcony at Motel Alić, where the cevapi is so good our guide from Sarajevo can’t hide his surprise, we can look over the town. The Muslim neighbourhood is to our right. The mosques have been rebuilt, but many buildings haven’t. While their simple existence suggests some harmony in the town, our guide says Srebrenica remains divided.

Many locals don’t like to acknowledge what happened here. Before the war, more than 30,000 people lived in the area, nearly 6000 of those in Srebrenica itself. Now there’s only about 13,000 in the area and 2000 in town. The population is still mainly Bosniak, but only just. Bosniaks once made up more than three quarters of the population. These days it’s just over half. After they were forced to flee during the war, it took until 2000 for the first Bosniaks to return to live permanently in Srebrenica.

There are further roadblocks to accepting what happened, and perhaps, moving on. Officially, the massacres at Srebrenica aren’t recognised as genocide. As recently as 2015, Russia vetoed an attempt to mark the 20th anniversary of the killings with a United Nations Security Council resolution condemning the crimes as genocide.

We don’t linger after our meal. On the drive out of town, down the same road we came in on, we pass the abandoned houses and a wall covered in graffiti reading in giant blue letters: PEACE.

How to visit

Srebrenica is about a 2.5/3-hour drive from Sarajevo. The Srebrenica Genocide Memorial is at Potočari, about seven kilometres from Srebrenica.

We visited the memorial and Srebrenica with BH Spirit tours. Because we were the only people who booked the tour that day, we had our own driver/guide and therefore some flexibility around how long we stayed at each stop.

It is possible to visit Srebrenica independently. There are buses from Sarajevo to Srebencia and some accommodation in town. Potočari is before Srebrenica, so you may be able to ask the bus driver to drop you off on the way to town, otherwise you can catch a taxi to the memorial.

If you can’t make it to Srebrenica but are interested in learning more about the events of 1995, there are excellent displays at Gallery 11/07/95 and the Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide in Sarajevo and the Museum Of War And Genocide Victims in Mostar.