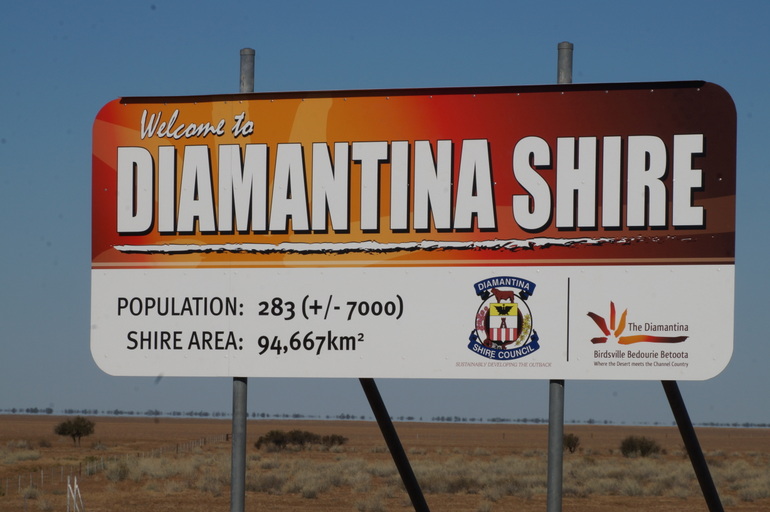

A sign on the outskirts of town declares the population as “115 (+/- 7000)”, although it was clear a while ago the people down here have a sense of humour.

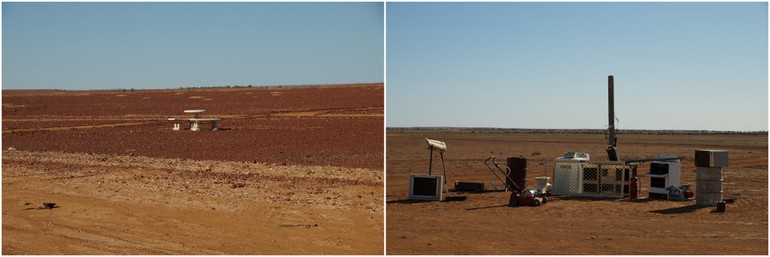

The Diamantina Shire boundary a couple of hundred kilometres north also advertised the fluctuating population. There was the assortment of random appliances including an oven, washing machine, microwave, television and lawn mower arranged at the turn off to a station.

A further 10 or so kilometres down the dirt highway sat an elegant picnic table set. In the middle of nowhere. Then there was the hanging mass of shoes covering a sign marking a private road. By the time you reach the sign for the bakery you wonder what you’re in for once you roll into Birdsville.

“Did you see a station wagon going the other direction?” the caravan park owner asks. We did. It stood out on roads that are four-wheel-drive territory. “That was a couple of backpackers who’ve been working here. Just left this morning.” Looking at a map it would be hard to imagine what would attract a couple of European working holiday makers here. But Birdsville’s location is why this town, which in the 19th century was a toll collection point for cattle moving between Queensland and South Australia, thrives years after Federation made its original purpose redundant.

Birdsville is the nearest town to Poeppel Corner, the intersection of the Queensland, Northern Territory and South Australian borders. Some of the most famous four-wheel-drive routes in Australia lead here, including the Birdsville Track, which travels through the Strzelecki Desert in South Australia, and the five-day journey over the 1140 dunes in the Simpson Desert.

But Birdsville is not just a pit stop for off-road enthusiasts. It’s an outback icon and enticing to curious travellers like me who want to see what goes on down here.

A photo of Big Red put the idea of visiting Birdsville in my head, but as I met more people on the outback road trip circuit I got the feeling it wasn’t an ordinary outback town. People willingly drive hundreds, if not thousands, of kilometres out of their way to come here. So many people told me I would love it and until I saw it for myself, I didn’t understand what could be so special. But they were right. It’s hard to explain why, but the town got under my skin. There were so many stories and quirks and a way of life that had you thinking ‘only in Birdsville’. It would take a long time to learn the secrets of a place like Birdsville, time that I’d one day love to have, but a day or two gives a glimpse into this remarkable town.

Mid-morning on a Monday in August the only caravan park is filling up. It’s pricey, but that’s expected. Everything in Birdsville comes at a premium: camp spots, fuel, food, beer. It’s a 1400-kilometre round trip to the nearest supermarket of a decent size. Most locals have their groceries delivered every few weeks from Adelaide. Plus, it’s the busy season. Since summer temperatures average a top of almost 40C (the record high is 49.5C), the tourist season in Birdsville is in the cooler months. I can’t bring myself to say ‘winter’ to describe a period when the temperature hovers around 20C, even if it can drop to zero at night.

A couple of hours before sunset we drive the 40 kilometres over badly corrugated roads to Big Red, the largest sand dune in the Simpson Desert. A sign warns us the trip, which doesn’t appear challenging compared to other routes in the area, isn’t always possible. Similar signs advise the condition of almost every road in and out of Birdsville. This part of the world is at the mercy of the elements – heat, wind, rain. The latter, even in mild form, can turn the roads to slush and isolate the town. Get stuck out here and it’s expensive. The bill for the recovery truck can easily total into the thousands.

It’s peak hour in the desert. Tyre tracks cover the dune’s plateau and plenty more will be added before the sun goes down.

There are two types of visitors who meet at the top of Big Red at this time of day: weary drivers racing to the summit from the west to mark the end of their cross-desert adventure, and those who came all the way here to dig their toes into the sand. After they’ve admired and enjoyed the icon, they move onto another – The Birdsville Hotel.

There were once three hotels in Birdsville, but now there’s just the one, opposite the town’s airstrip. It’s a matter of metres from the tarmac to the front step of the pub. The ruins of a second hotel, the Royal, are fenced off down the road. The Birdsville Hotel is 130 years old and, like many of the outback’s isolated watering holes, has become a must-see. Visitors are enticed by the promise of a peek into outback life and the chance to chat to a local. This pub doesn’t disappoint, although at this time of year the tourists far outnumber those who call Birdsville home.

On this Monday night the bar and restaurant is full. The wait for food is at least an hour. No one minds. The following morning it’s a lot quieter. Slow enough to have a chat with the barman and nose about the place a bit. The barman tells us the crowd of several hundred last night was unexpected. But they aren’t complaining. Once the heat hits the crowds will disappear.

The main bar is full to the brim with….stuff: old beer cars, flags, funny signs, framed newspaper articles. Worn Akubras line the roof above the bar, acknowledging people who have lived in Birdsville for at least a year. I pop some coins in a donation box for the Royal Flying Doctors Service – a small price to pay for photographing an institution.

The barman tells us all of it will soon come off the walls – every last thing – when the town is engulfed for the annual Birdsville Races on the first weekend of September. The event has attracted up to 9000 people, but the average is 7000, which explains those population signs. The entire town will be taken over. The caravan park will be booked out, the airstrip filled with planes and tents, and the wide empty street that I can walk along undisturbed will be packed and covered in beer cans. It’s a tradition for punters to drop their empty cans on the ground.

The event is part of the Simpson Desert Racing Carnival, which includes races at Bedourie and Betoota. Even in 2007, when the races were cancelled because of the equine influenza outbreak, about 3000 people showed up anyway. The race course is a couple of kilometres south of the town. Three weeks out from the event of the year a few workmen are pottering about. It’s hard to imagine 9000 people passing through that corrugated iron entrance.

Over a lamington on the verandah of the Birdsville Bakery we watch the town go through its morning routine. Engines are checked, water topped up, safety flags attached. Out the front of the bakery sits a blue 1963 Volkswagen Beetle named Onslo. In 2012, Kelly Theobald and her partner Sam drove the VW from Birdsville to Mt Dare. Yep, that thing made it across the Simpson Desert without a tow truck in sight. Kelly wrote a children’s book based on the story and both she and Onslo remain in Birdsville. The vintage car is a bit of an attraction and it certainly stands out among the masses of four-wheel-drives. But somehow the quirky scene makes sense in Birdsville.

The bakery is known for its camel pies, but coffee and breakfast is the order of choice in the early hours as visitors prepare for what will most likely be a long day of driving. We watch as a convoy of four-wheel-drives, orange flags flapping, heads for the desert.

A few hours later we hit the road ourselves, retracing our steps through the Diamantina Shire, past the shoes, the picnic table and the shrine of appliances.

1 Comment

I want to go to there.